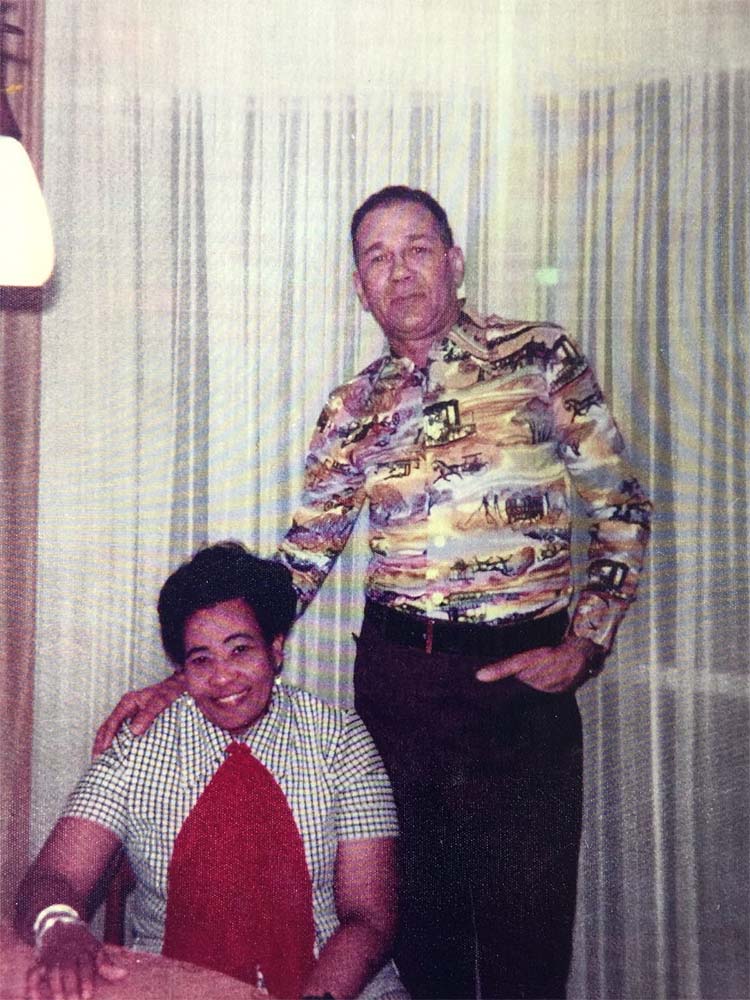

I sat with my grandmother one afternoon when I was 10. I remember wearing a blue shirt and pink pants. She was braiding my hair – I sat on the floor and she sat on chair bent over, and, in her usual straightforward way, pulled back her lips to reveal four missing teeth in her lower jaw. “Dada cuffed me,” she said, as if it were just another fact of life. Her husband had knocked her teeth out, over the weekend but she had carried that and many incidents of domestic violence with her for years, quietly. I remember sitting there, stunned, unsure of what to do with that information. I didn’t know whether to tell my Mom or to keep it quiet, bury it deep inside, like so many women in our family seemed to do.

Years later, when I was 19, I found myself in a situation that eerily mirrored my grandmother’s. My fiancé, in a jealous rage, grabbed me and threw me over a table. I landed hard on the ground, and as I lay there, dazed and hurt, he stood over me, blaming me for making him angry. The worst part was that this happened in public. People saw, but no one stepped in to help. No one asked if I was okay. After it was over, I walked home, a two-hour and twenty-minute walk, with so many emotions competing for top spot inside me—anger, sadness, confusion—but mostly, a fierce commitment that I would never let this happen again.

In that moment, I realized that domestic violence is not just something that happens to “other people.” It can and does happen to many of us, regardless of where we’re from or how strong we think we are. It’s insidious, creeping into our lives in ways that often feel familiar, even normal. And, unfortunately in the West Indian culture, this issue is hidden, not talked about yet generationally accepted.

The statistics are concerning: 1 in 3 West Indian women will experience domestic violence in their lifetime. It’s an epidemic rooted in the culture of colonial male dominance, where patriarchy and misogyny are passed down and ‘understood’. Too often, women are told that if a man hits you, it’s your fault. That you did something to provoke him. From a young age, we are conditioned to be silent, to bear the burden quietly, to hide our bruises and our pain so as not to become the topic of rumours and shame.

My grandmother’s story wasn’t unique. Her missing teeth were part of a long line of whispered stories, of women who were taught to endure rather than speak out. And for so long, I carried that silence too. But the truth is, domestic violence thrives in that silence. The culture of whispers, the quiet suffering, the unspoken shame—it all feeds into a system that allows abuse to continue unchecked.

We need to break that cycle. To the women reading this, especially my West Indian sisters, I want you to know that you are not alone. Whether you’ve experienced abuse or are watching someone you love go through it, your voice matters. Your story matters. We can’t let shame or fear keep us silent.

Breaking the stigma of DV is not easy but breaking the wheel of generational trauma is our responsibility. We deserve better and demand better—for ourselves, for our grandmothers, for our daughters, for our nieces and nephews, sons and brothers. Ending domestic violence starts with acknowledging it is not your fault, you are not the problem and you did not deserve any of it. Physical, psychological, and emotional abuse – is ABUSE. Start by trusting yourself. Questioning whether they had a bad day, or you said or did something to deserve it – trust yourself to know when that voice inside of you is screaming ‘MAKE IT STOP!’ Next, consider speaking to a trusted friend, colleague, therapist, counselor, or relative. You may not be as alone as you may think. The burden of secrecy weighs heavy, lighten the burden. Wishing all those who read this and if this resonates with you – you are not alone.

November is Domestic Violence Awareness Month in Canada.

Find family violence resources and services in your area

Fostering Violence Prevention and Well-Being for Black Women, Families and Communities

Sheryl Johnson – she her pronouns – Born and continue to reside on the stolen territories of Treaty 13. Racialized dark-skinned settler of West Indian and Eastern European heritage. Proud to be the granddaughter of Gran Gran and Da Da pictured.